The pockets of snow scattered among the grey rocks are getting larger as your 4x4 climbs the mountain path. The temperature reading on the dashboard says it’s minus ten outside, making you appreciate the vehicle’s smart heating system, perfectly calibrated to your core temperature.

The gravel path looks icy. You stare down into the deep ravine to your left, littered with jagged granite outcrops. The roadside barrier looks pretty decrepit. You are glad you’re in the safe hands of the AI driver and not having to negotiate this treacherous track manually.

You recognise where you are. You’ve patrolled this station several times over the last few months, providing force protection for various technical capabilities. You know that round the next corner, the road, such as it is, comes to an end. You’ll be on foot from there on.

The vehicle comes to a halt and your seatbelt unclicks automatically. Your fellow gunner, in the seat next to you, hops out of the door and moves round to the rear of the vehicle. You grab your camouflaged jacket and put your gloves on before opening the door and stepping into the frigid air. A plume of your breath gathers and then drifts in the cold breeze. By the time it dissipates, the camouflage on your jacket and trousers has shifted from greens and browns, to whites and greys.

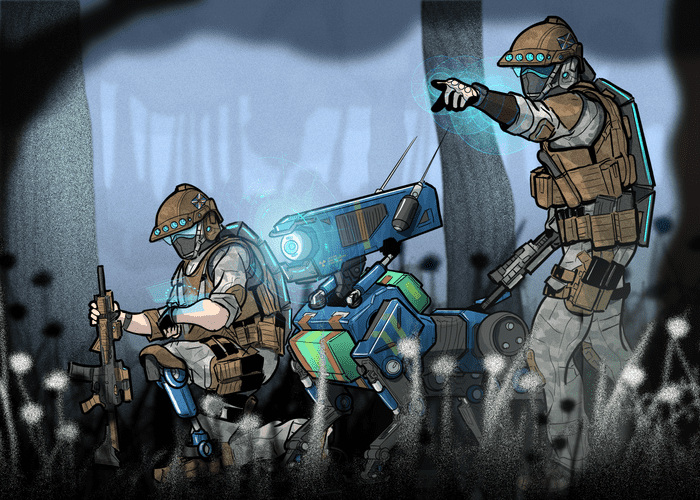

Your colleague emerges from behind your 4x4 having retrieved the third member of your team. A quadrupedal robot crouches by his feet, its hinged legs coiled for action.

“Cavall, lead off at walking speed,” your colleague commands. “Take us to the node station.”

The robot, here to carry out a diagnostic assessment of the node station, begins trotting up the hill, taking a gentle zig-zagging route for the benefits of its masters. You know it is capable of running up much steeper gradients. You are about to stride off in its wake, when your colleague points out that the lace on your right boot is loose. You stoop to fasten it and then instinctively check the other foot, before remembering the futility of doing so. Instead, you brush snow off the metal blade of your prosthetic left foot.

As you and your colleague continue to follow Cavall up towards the summit of the mountain, the route becomes more difficult. The path cuts back on itself and the ground is icy. Cavall waits for you obediently just above the frozen section of the path. You place your real foot on the ice and it starts to slide, the rubber tread of your boot unable to provide any traction. Your colleague looks at you expectantly. You place your prosthetic leg onto the ice and hear a crunch as its retractable titanium studs emerge and bite into the ice, giving you good purchase. You reach back and grab your colleague’s hand, helping him clamber up the slope.

Not for the first time on this deployment, you wonder whether the comms and infrastructure guys deliberately selected the most inaccessible places to drop all of the network nodes. They claim that they needed to site them the right distance apart and that they have to be unobstructed by terrain, but you’re pretty sure they just wanted to make it as difficult as possible for you and the other members of your squadron to patrol the whole mesh network.

The node station you are checking on now has apparently had some strange readings recently. Your job is to get up there, check on it and plug Cavall into it to do some diagnostics. He’s stopped ahead of you again in a thicket of fir trees. You and your colleague have started slowing down a bit, the air is noticeably thinner up here and the trees are becoming more sparse. Your colleague reaches Cavall and examines the data screen on his flank. He looks concerned.

“Cavall has picked up some people in the area,” he explains. “Four of them. Can’t imagine there are any hikers out in this weather.”

You decide to send Cavall forward to check, while communicating this information to the ops room. To execute these actions, you roll up your sleeve slightly to give you better access to your smartwatch. You shake your arm twice to activate its projected screen, which displays on the back of your gloved hand, and tap the various commands to provide Cavall with his instructions and relay your intelligence back to the ops room.

Still within the cover of the trees, you set up a position to observe Cavell as he progresses up the mountain in stealth mode. You pull your glasses out of your pack and put them on while your colleague keeps watch around your position. After a few seconds of fiddling with your smartwatch you have everything set up to view the imagery coming from Cavell’s cameras.

To begin with, everything is blurred and jerky, then the video settles. You have a clear view up the mountainside from Cavall’s perspective via your glasses. You can just make out the rectangular grey node container nestled in between some large rocks on the mountain’s crest. You can’t be sure, but you think you notice movement there. You tap on the relevant icon on the back of your hand and the view through Cavell’s cameras switches to infrared. Everything in the robot’s field of vision is blue or green, except for the cuboid network node, which glows yellow and two unmistakable orange and red blobs in the centre of the picture. Someone is interfering with the node.

You tap a few more times on the back of your glove, ensuring Cavall uses his sensors to collect as much data as possible. You have a brief hushed discussion with your colleague about whether to engage the saboteurs. He is in contact with the ops room, who are telling you to stay put until additional support arrives. You become aware you can only see two figures in your infrared view. Cavall initially indicated there were four people present.

You use your smartwatch controls to shift the infrared view to a small frame in your peripheral vision, allowing you to see the world around you with your own eyes. You and your colleague now have your rifles shouldered and are both prone on the cold ground, facing in opposite directions. You feel the internal heating in your jacket come on in response to your dropping body temperature. You press the pad above your breast pocket to kill the heating. Better to be cold than give off a larger heat signature.

You continue to survey your surroundings, while intermittently keeping one eye on the imagery being provided by Cavall. He is visually scanning, slowly rotating his head through 360 degrees and providing panoramic coverage. You can’t be sure, given the size of the marginalised image in your glasses view, but on one sweep you’re pretty sure you see another two orange and red blobs in addition to the two loitering by the network node.

Your watch vibrates against your wrist and you notice your view from Cavall’s camera is on the move - quickly. He can run about 50km/h, depending on the terrain, and you think he must be trying his best to reach that speed now. You hear a crisp eruption of automatic gunfire, like the air being torn somewhere. There’s another short burst, some shouting and then something like a loud snare drum, a grenade maybe. Cavall’s imagery goes offline.

You wait, your heart hammering in your chest. You finger the trigger on your rifle and roll your weight from side to side, getting comfortable. Seconds pass, or maybe minutes. You blink a few times to make sure you can see clearly. More time passes. Any minute now, you can feel it.

You stare hard down your sight, and then you see it, something moving through a cluster of saplings. You fix it and whisper into your smartwatch, instructing it to change your sight to thermal imaging. The target looks strange, parts of it are deep red, but its shape is too regular, the lines are too straight. You zoom in and recognise what is hobbling back in your direction on three legs.

Cavall pauses about 250 metres away, and then limps off in a different direction, following the emergency protocol designed to avoid leading anyone back to your position. You’re suddenly touched by his selflessness and realise how glad you are that he’s still functioning, still alive.